Polarimetric signatures of accreting black holes

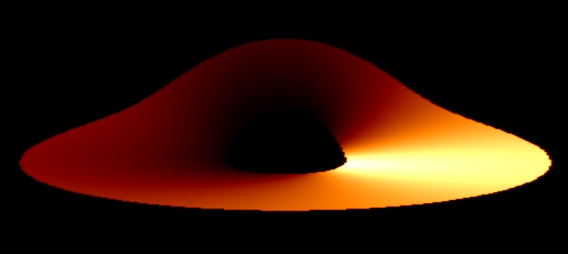

Model of a thick accretion disk around massive black holes, seen by an observer at infinity. The color refers to the synchrotron radiation produced with a vertical magnetic field.

Supervisor : Dr. Alexandra Veledina, post-doctoral fellow ,Tuorla observatory, University of Turku, Finland.

This project led to a published paper in a journal.

The black holes are compact celestial objects whose mass can be several times that of the sun. The gravity exerted is such that, from a certain surface called the event horizon, nothing can escape, not even light, which explains their name. Although it may seem paradoxical, it is possible to observe them. These objects are surrounded by an accretion disc, whose constituent matter spins around the black hole to fractions of the speed of light. The disc emits light. This is what has enabled the Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration to obtain in 2019 the first image of a black hole, or more precisely the first image of a black hole accretion disc (see cover).

The study carried out during this internship concerns the modelling of radiation signature of matter near black hole, similar to that of M87* observed in 2019. To study a black hole theoretically, the most suitable tool is general relativity, considering gravity as a reason for deformation of space time. The framework used to study a massive, non-rotating spherical object is the Schwarzschild metric, which characterises the deformation of space-time caused by such an object. The light emanating from the accretion disc follows a trajectory to reach the observer. These paths are not simply straights lines as in the limit of flat space-time, but are curved and constitute geodesic lines. Calculation of photon paths can be done exactly via ray tracing, or approximately via analytical methods. We thus obtain the image of the accretion disc perceived from different inclinations, by an observer placed at infinity.

Light can be considered as an electromagnetic wave, oscillating through space. For different photons, the electric field differs, but if there is a preferred direction, the light is polarized. This is subject to the effects of special and general relativity. Thus the polarisation of the light emitted by the fluid constituting the accretion disc is not the same as that measured by the observer. By using basis changes, we were able to obtain the polarisation angle measured in the observer’s sky. By first approximating an infinitely thin accretion disc, then with a non-zero thickness, we were able to obtain an image of an accretion disc around black hole, as well as the degree and angle of polarisation at each point.